Democrats Have a Religion Problem

A conversation with Michael Wear, a former Obama White House staffer, about the party’s illiteracy on and hostility toward white evangelicals

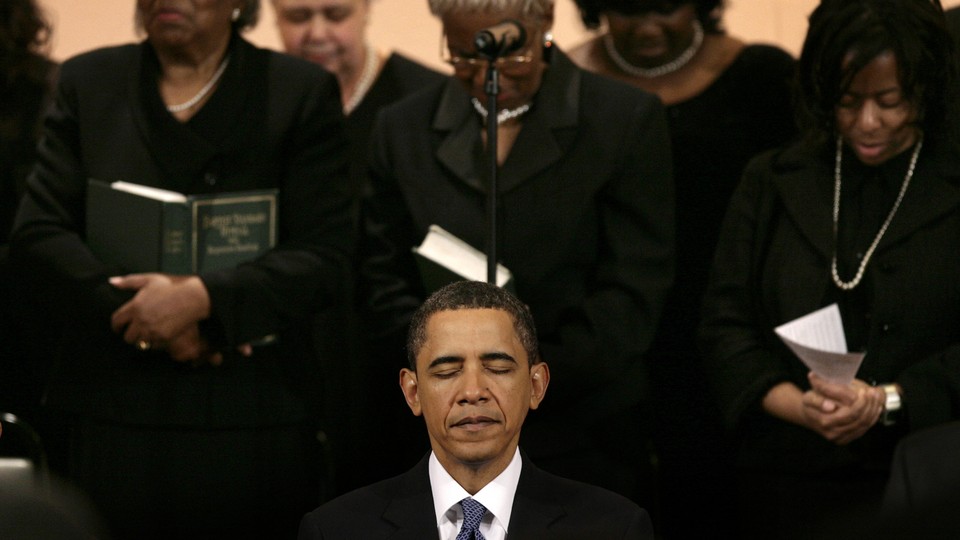

There aren’t many people like Michael Wear in today’s Democratic Party. The former director of Barack Obama’s 2012 faith-outreach efforts is a theologically conservative evangelical Christian. He is opposed to both abortion and same-sex marriage, although he would argue that those are primarily theological positions, and other issues, including poverty and immigration, are also important to his faith.

During his time working for Obama, Wear was often alone in many of his views, he writes in his new book, Reclaiming Hope. He helped with faith-outreach strategies for Obama’s 2008 campaign, but was surprised when some state-level officials decided not to pursue this kind of engagement: “Sometimes—as I came to understand the more I worked in politics—a person’s reaction to religious ideas is not ideological at all, but personal,” he writes.

Several years later, he watched battles over abortion funding and contraception requirements in the Affordable Care Act with chagrin: The administration was unnecessarily antagonistic toward religious conservatives in both of those fights, Wear argues, and it eventually lost, anyway. When Louie Giglio, an evangelical pastor, was pressured to withdraw from giving the 2012 inaugural benediction because of his teachings on homosexuality, Wear almost quit.

Some of his colleagues also didn’t understand his work, he writes. He once drafted a faith-outreach fact sheet describing Obama’s views on poverty, titling it “Economic Fairness and the Least of These,” a reference to a famous teaching from Jesus in the Bible. Another staffer repeatedly deleted “the least of these,” commenting, “Is this a typo? It doesn’t make any sense to me. Who/what are ‘these’?”

I spoke with Wear about how the Democratic Party is and isn’t reaching people of faith—and what that will mean for its future. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Emma Green: Many people have noted that 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump in this election. Why do you think that was?

Michael Wear: It shows not just ineptitude, but the ignorance of Democrats in not even pretending to give these voters a reason to vote for them. We also need to have a robust conversation about the support or allowance for racism, misogyny, and Islamophobia in the evangelical tradition.

Many of those 81 percent are accommodating cultural changes in America that are deeply problematic. Liberals have been trying to convince Americans, and evangelicals in particular, that America is not a Christian nation. The 2016 election was evangelicals saying, “Yeah, you’re right! We can’t expect to have someone who is Christian like us. We can’t expect to have someone with a perfect family life. What we can expect is someone who can look out for us, just like every other group in this country is looking for a candidate who will look out for them.”

There’s a lot of conversation in Christian circles about Jeremiah 29, which is Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles in Babylon. The message Jeremiah had, and that the Lord had, for the exiles is that they should seek the peace and prosperity of the city where they’ve been planted, and multiply—they should maintain their convictions for the flourishing of others. The concern I have, and that many others have, is that in this time of cultural transformation in America, you’re going to have many evangelicals who just become Babylonians.

Green: Why is it, do you think, that some liberals—and specifically the Democratic Party—have been unwilling to do outreach to people who hold particular kinds of theological points of view?

Wear: They think, in some ways wrongly, but in other ways rightly, that it would put constraints around their policy agenda. So, for instance: You could make a case to evangelicals while trying to repeal the Hyde Amendment, [which prohibits federal funding for abortion in most circumstances,] but that’s really difficult. Reaching out to evangelicals doesn’t mean you have to become pro-life. It just means you have to not be so in love with how pro-choice you are, and so opposed to how pro-life we are.

The second thing is that there’s a religious illiteracy problem in the Democratic Party. It’s tied to the demographics of the country: More 20- and 30-year-olds are taking positions of power in the Democratic Party. They grew up in parts of the country where navigating religion was not important socially and not important to their political careers. This is very different from, like, James Carville in Louisiana in the ’80s. James Carville is not the most religious guy, but he gets religious people—if you didn’t get religious people running Democratic campaigns in the South in the ’80s, you wouldn’t win.

Another reason why they haven’t reached out to evangelicals in 2016 is that, no matter Clinton’s slogan of “Stronger Together,” we have a politics right now that is based on making enemies, and making people afraid. I think we’re seeing this with the Betsy DeVos nomination: It’s much easier to make people scared of evangelicals, and to make evangelicals the enemy, than trying to make an appeal to them.

Green: I’ve written before about the rare breed that is the pro-life Democrat. Some portion of voters would likely identify as both pro-life and Democrat, but from a party point of view, it’s basically impossible to be a pro-life Democrat. Why do you think it is that the party has moved in that direction, and what, if anything, do you think it should do differently?

Wear: The spending that women’s groups have done is profound. 2012 was a year of historic investment from Planned Parenthood, and the campaign in 2016 topped it.

Number two, we’re seeing party disaffiliation as a way of signaling moral discomfort. A lot of pro-life Democrats were formerly saying, “My presence here doesn’t mean I agree with everything—I’m going to be an internal force that acts as a constraint or a voice of opposition on abortion.” Those people have mostly left the party.

Third, I think Democrats felt like their outreach wouldn’t be rewarded. For example: The president went to Notre Dame in May of 2009 and gave a speech about reducing the number of women seeking abortions. It was literally met by protests from the pro-life community. Now, there are reasons for this—I don’t mean to say that Obama gave a great speech and the pro-life community should have [acknowledged that]. But I think there was an expectation by Obama and the White House team that there would be more eagerness to find common ground.

Green: One could argue that among most Democratic leaders, there’s a lack of willingness to engage with the question of abortion on moral terms. Even Tim Kaine, for example—a guy who, by all accounts, deeply cares about his Catholic faith, and has talked about his personal discomfort with abortion—fell into line.

How would you characterize Democrats’ willingness to engage with the moral question of abortion, and why is it that way?

Wear: There were a lot of things that were surprising about Hillary’s answer [to a question about abortion] in the third debate. She didn’t advance moral reservations she had in the past about abortion. She also made the exact kind of positive moral argument for abortion that women’s groups—who have been calling on people to tell their abortion stories—had been demanding.

The Democratic Party used to welcome people who didn’t support abortion into the party. We are now so far from that, it’s insane. This debate, for both sides, is not just about the abortion rate; it’s not just about the legality of it. It’s a symbolic debate. It’s symbolic on the pro-choice side about the autonomy of women and their freedom to do what they want with their bodies. On the pro-life side, they care not just about the regulations around abortion, but whether there’s a cultural affirmation of life.

Even the symbolic olive branches have become less acceptable.

Green: If you were talking to a secular Democrat who is skeptical about the need to do outreach to conservative evangelicals or make a compromise on language surrounding social issues like abortion, same-sex marriage, etc., what would you say?

Wear: It’s sad that this is a throwaway response, but it’s the duty of statesmanship. It’s the duty of living in a pluralistic society to make a case to all folks.

The second would be that America is still a profoundly religious nation. There are reports that high-level Democratic leadership was not interested in reaching out to white Catholics. And they sure didn’t have a lot of interest in white evangelicals. That’s a huge portion of the electorate to throw out. So if the civic motivation doesn’t get you, let me make the practical argument: It doesn’t help you win elections if you’re openly disdainful toward the driving force in many Americans’ lives.

The Democratic Party is effectively broken up into three even thirds right now: religiously unaffiliated people, white Christians who are cultural Christians, and then people of color who are religious.

Green: And religious minorities.

Wear: Well, right, but because of their numbers—I’m speaking in general terms.

Barack Obama was the perfect transitional president from the old party to the new. He could speak in religious terms in a way that most white, secular liberals were not willing to confront him on. He “got away with” religious language and outreach that would get other Democratic politicians more robust critiques from the left. He was able to paper over a lot of the religious tensions in the party that other, less skilled politicians will not be able to paper over.

Green: You’re a little bit of a man in the wilderness. You have worked for the Democratic Party, but you have conservative views on social issues, and you are conservative in terms of theology. There just aren’t a lot of people like you. Does it feel lonely?

Wear: It’s not as lonely as it might appear on the outside.

One of the things I found at the White House and since I left is this class of people who aren’t driving the political decisions right now, and have significant forces against them, but who are not satisfied with the political tribalism that we have right now. I think we’re actually in a time of intense political isolation across the board. I’ve been speaking across the country for the year leading up to the election, and I would be doing these events, and without fail, the last questioner or second-to-last questioner would cry. I’ve been doing political events for a long time, and I’ve never seen that kind of raw emotion. And out of that, I came to the conclusion that politics was causing a deep spiritual harm in our country. We’ve allowed politics to take up emotional space in our lives that it’s not meant to take up.

Certainly, it would be a lot more comfortable for me professionally if I held the party line on everything. Politically, I definitely feel isolated. But a lot of people feel isolated right now. And personally, I don’t feel lonely because I find my community in the church. That has been a great bond.